Post-Covid, New York City has become a different city. But how so? How did the worldwide health crisis impact public spaces, amenities and everyday life? To answer these questions, ESENDOM spoke to Nick Bacon about urban planning, architecture and the impact of the Covid pandemic on New York City. Bacon wears many hats; in addition to being an urban studies scholar, Bacon is a labor activist, educator and editor originally from Connecticut but he is also a New Yorker at heart with a soft spot for New York’s public spaces, Dominican food as well as the cultural diversity that makes the city unique.

By Amaury Rodriguez

I’m going to state the obvious: cities underwent a huge change during the pandemic. Can you talk about how New York changed and at the same time, what remains unchanged in the “city that never sleeps”?

Sometimes, when I walk down Broadway in Upper Manhattan, it feels like the pandemic never happened. In neighborhoods like mine, the urban vivacity that only comes from a density, diversity, and scale unique to New York City is still apparent. Our apartments, still too tiny to really keep us inside, seem to project us outside, where we’re amongst everyone else. The streets we land on are still thriving with life. The urban ‘feeling’ that we lost during early Covid, locked away as we were in rooms too small to share personal and work functions, is back. But look a little deeper, and you start to see it - the ghost storefronts of small businesses that seemed like they’d be open a thousand years, only to shutter mere months into the crisis; the increased homelessness that proliferated around here right after landlords regained the right to evict tenants; syringes, pipes, violence - vestiges of addictions that erupted and multiplied during the traumas of 2020.

“The streets we land on are still thriving with life. The urban ‘feeling’ that we lost during early Covid, locked away as we were in rooms too small to share personal and work functions, is back.”

You see the survival of pandemic urbanism at the other end of Broadway too, where I work both as a teacher and union activist in lower Manhattan. Here, Wall Street’s buildings stand tall and glitzy as ever as companies bring in record profits. But the presence, at least of once ubiquitous white collar workers, are few and far between. Sometimes, walking in FiDi (Financial District), it feels like Sunday morning in a vacated suburban office park, but it’s 4:00pm on a Monday in the big apple. Where is everyone? Even [Eric] Adams seems to have given up on keeping office workers in Manhattan, signing labor contracts that allow some public employees to work up to two remote days a week. But New York’s apartments for the working class were never conceived as places to live and work; they’ve always been too small, too crowded, to have both functions. ‘Work-from-home’ culture is diametrically opposed to living in the city limits; the remote moment therefore is as suburb-inducing as the GI bill, flushing out urbanites and would-be urbanites into slightly bigger boxes in Jersey, Long Island, Westchester, Connecticut, and Indiana.

Despite the clear post-Covid vacancies that remain in New York, rents are higher than ever. All those calls to redevelop unused offices into affordable housing are basically going unheeded, probably because the rentier class doesn’t think they’ll make enough money out of it. And it’s not just rents that are too high - it’s everything. The simple pleasure of sitting down at a no-frills lunch counter and ordering beef stew or chicken and rice, once an everyday part of New York ‘street’ culture, is now a ‘luxury'. As the small businesses around us disappear or become functionally unaffordable to the working class, the street that used to draw us out throws us back into our apartments, which risk becoming mere cul-de-sacs in the sky.

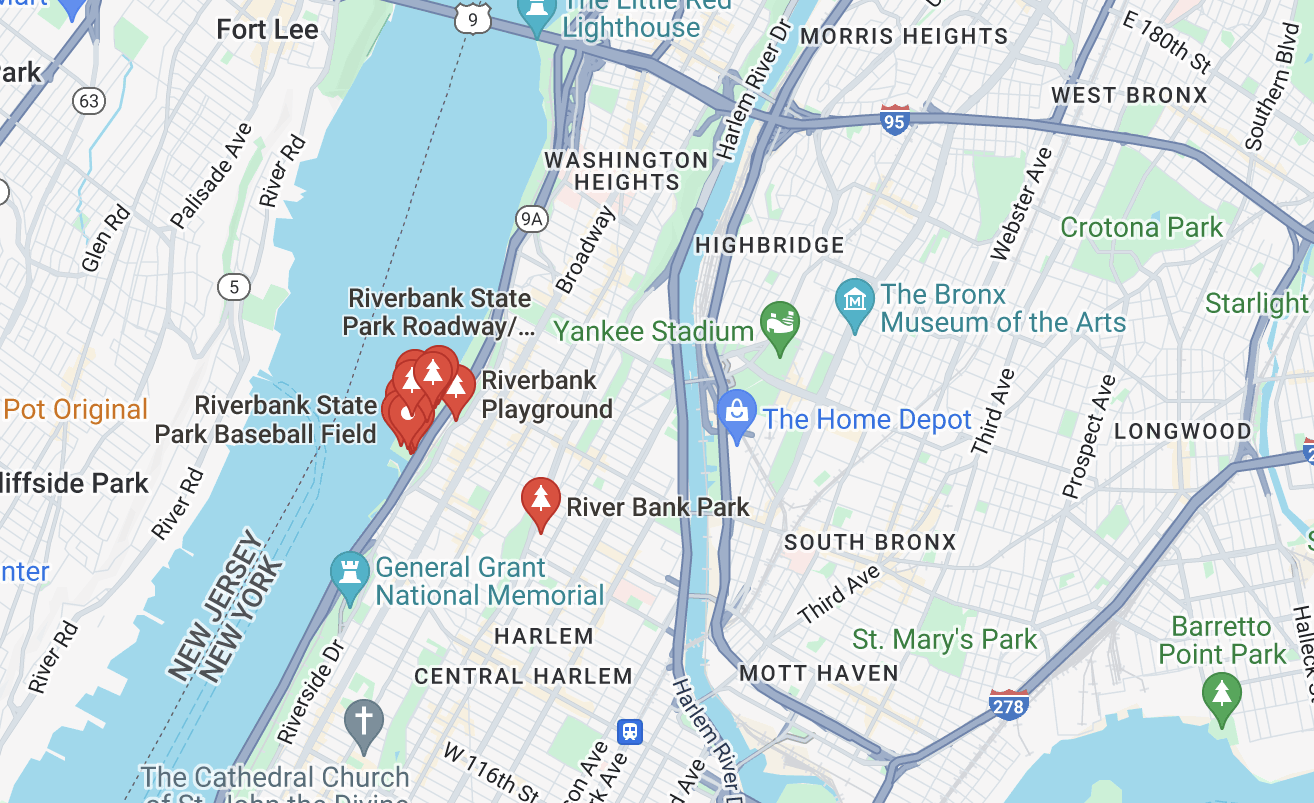

New York is known for its public parks and amenities. In your work you explore the meaning of Riverbank Park within the fabric of the city. First, why did you focus on Riverbank Park? And second, how can we rethink state parks to make them more democratic spaces?

Most of my published work is about the exploitation of urban peripheries in ways that directly contradict the values of those who live there. For example, about ten years ago I published several pieces about a paradoxical new form of urbanism by which lower income post-industrial satellites started to finance massive stores that made most of their money selling firearms (and the rest of it selling camping gear). These complexes were the epitome of anti-urbanism, and to be sure, were not meant for the local population. The stores were meant for suburbanites, exurbanites, and day-tourists who valued the centrality of shrinking cities, many of which still had extensive highway access but no longer had extant industrial uses. The populations who lived in these shrinking cities often couldn’t afford to pay for services that they actually wanted, and so municipalities paid a lot of money to develop complexes to serve outsiders with the hope of generating economic multiplier effects and eventually growing tax revenue. Generally, their hopes didn’t pan out. And there was a particular irony here, because not only did residents not desire the gun stores, but many of these cities were plagued by gun violence and the politicians/residents were against firearms outright. The fact that cities trying to end gun violence were putting up gun stores as urban renewal projects just boggled my mind. It was a direct affront to their values - and very much indicative of the new type of urbanism.

Riverbank State Park was initially interesting to me because it was such an opposite situation. Here we had a necessary use that begat a locally relevant series of additional uses (rather than a frivolous firearm store). Specifically, Riverbank sits atop a sewage treatment center necessary for the western side of Manhattan. What was not necessary, of course, was to build it in West Harlem instead of a more well-to-do west-side neighborhood. So after hard-fought community advocacy, activists achieved a compromise to the pollution that the sewage treatment center would engender locally by placing a park on top. But it’s unlike most parks you’ve ever seen, which generally aren’t surrounded by sewage treatment machinery. Riverbank, which is overlaid atop this infrastructure, isn’t a bed of green, but a series of athletic and artistic venues meant to directly support the physical and cultural health of those who live in the neighborhood. It’s imperfect. Not everyone is going to necessarily find a use for themselves here, as the spaces have been prescribed for particular activities, though the range of such prescribed uses is astounding (e.g. basketball, track, soccer, skating, weightlifting, swimming, occasional music/theater, etc). On the other hand, interested persons may find that they’re priced out of actually using Riverbank, as many of the uses (e.g. the tennis court, the gym, etc) require added fees that range from modest to potentially prohibitive. Sometimes different groups also compete to use the same space, as occurred between hockey players and figure skaters over the ice skating rink. And there are indications that some of the infrastructure is in disrepair or no longer being used. Therefore, Riverbank provokes several questions: what uses should be privileged, how do we budget to reproduce the uses of the park–many of which require ongoing maintenance and staffing, and who gets to use the park and when?

Riverbank provokes such questions because it is an inherently political space - a space to be used rather than just seen, and to be used differently by competing members of a changing community in a historical moment very different from that which existed when it was planned and constructed. To that end, Modern parks in New York could learn a lot from Riverbank. Today, the majority of park funding is funneled into megaprojects designed for purely aesthetic enjoyment, generally for tourists. Questions embedded in the fabric of Riverbank aren’t provoked at all by glossy monuments that most New Yorkers experience themselves like tourists - infrequently, quickly, and passively. To the extent that neighborhood parks still exist, they aren’t built at the astounding scale of Riverbank anymore. The few new parks/squares being created are generally smaller, easy to maintain, and prescribe mostly passive uses. They aren’t tourist spectacles in the same way as, say, the High Line or Little Island, but they aren’t significant sources of use horizons either, as is the case with Riverbank. That lack of clear ‘use value’ leads often to underutilization and sometimes co-option by other uses, which is one reason why many such parks end up being converted into havens for illicit drug use.

“Riverbank provokes such questions because it is an inherently political space ”

Democracy doesn’t happen in spaces which purely induce spectacle or passivity, but in spaces that can be used by residents who value them. That’s how we get parks to increase, rather than decrease, quality of life for New York’s working class communities.

On the topic of New York, what authors do you recommend to our readers?

I originally came to New York to study with urban theorists at the CUNY Graduate Center, some of whom I still think wrote the best work I’ve personally read on cities, and New York City specifically. Neil Smith, who died while I was a student, wrote among the most influential articles I’ve ever read on the subject of gentrification in this city. Some of those articles are collected in an edited volume called The Revanchist City. One of his students, now a professor in his own right, Julian Brash, wrote a phenomenal book on the Bloomberg years, entitled Bloomberg’s New York. We might be two mayors out from Bloomberg, but the ramifications of his sort of urban policy are still there. It’s a book very much still worth reading. Ida Susser, who is on my committee if I ever get around to finishing my Ph.D., wrote a book called Norman Street which is an older ethnographic take on the right to the city in Greenpoint-Williamsburg. It was recently republished and is well worth a read. And then there’s the late Marshall Berman’s All that is Solid Melts into Air, a book about far more than just New York, but which includes one of the best pieces on Robert Moses I’ve ever read. For a recent book that writes to a popular audience on changing New York (and does so quite well), see Jeremiah Moss’s Vanishing New York.

Lately, I’ve become more involved in the NYC union movement, both as a writer (here’s one of my more recent pieces) and as an activist (I co-chair an organization called New Action Caucus of the UFT). Labor and labor struggles, it turns out, have much to do with how residents can access and experience New York. There are good monographs on particular labor moments in New York, such as Jerald Podair’s The Strike that Changed New York, which focuses on the infamous 1968 teachers strike in Ocean-Hill Brownsville. There are good books on labor more generally. Josh Freeman wrote the ‘book’ so to speak on labor in NYC with Working Class New York - well worth a read.

And there’s so much more. The city I originate from, Hartford, Connecticut, had very little written about it. My edited volume on the subject, Confronting Urban Legacy, tried to help rectify that. What’s great for readers in New York is that there truly is no dearth of things to read about our city. I can happily say that there are far more books I still have on my shelf waiting to be read than what I’ve read already.

__

Nelson Santana and Emmanuel Espinal contributed to this interview.